Scientists at the University of Connecticut have unveiled a novel imaging system, the Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager (MASI), that bypasses the limitations of traditional lens-based optics to achieve sub-micron 3D resolution without the need for lenses. Inspired by techniques used in radio astronomy – including those that enabled the first image of a black hole – MASI promises transformative applications in forensics, medical diagnostics, and remote sensing.

Overcoming a Longstanding Technical Barrier

For decades, high-resolution optical imaging has been constrained by the physics of light. Conventional synthetic aperture imaging (SAI) requires precise synchronization between multiple sensors, a feat easily achieved at radio wavelengths due to their longer wavelengths. However, at visible light wavelengths, where details of interest are measured in micrometers, such synchronization becomes nearly impossible to maintain physically.

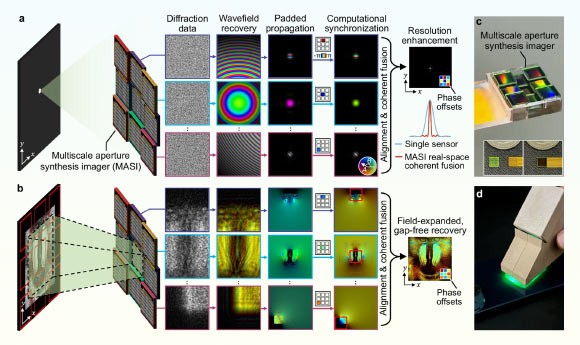

MASI solves this by shifting the synchronization burden from hardware to software. Instead of demanding that sensors operate in perfect physical synchrony, it allows each sensor to measure light independently. Computational algorithms then stitch this independent data into a coherent, ultra-high-resolution image. The process is analogous to multiple photographers capturing a scene and allowing software to combine their raw data into a single, highly detailed reconstruction.

How MASI Works: Diffraction, Not Refraction

Conventional imaging relies on lenses to focus light. MASI takes a fundamentally different approach: it uses an array of coded sensors positioned in a diffraction plane to capture raw diffraction patterns. These patterns contain both amplitude and phase information, which are computationally recovered. The system then digitally propagates these wavefields back to reconstruct the image.

The key innovation lies in computational phase synchronization. Instead of physically aligning sensors, MASI iteratively adjusts the relative phase offsets of each sensor’s data in software to maximize overall coherence. This eliminates the diffraction limit and other constraints imposed by traditional optics. The result is a virtual synthetic aperture that can be larger than any single sensor, enabling unprecedented resolution and wide field coverage.

Implications and Scalability

The benefits of lens-free imaging are significant. Traditional lenses force designers into trade-offs: higher resolution requires closer proximity to the object, limiting working distance and making certain tasks impractical. MASI, by contrast, can capture diffraction patterns from centimeters away, reconstructing images at sub-micron levels.

“This is akin to examining the fine ridges on a human hair from across a desktop instead of bringing it inches from your eye,” explains Professor Guoan Zheng, senior author of the study. The system also scales linearly, meaning that increasing resolution does not require exponentially more complex hardware, unlike traditional optics. This scalability suggests potential for even larger arrays and unforeseen applications in the future.

The team’s findings, published in Nature Communications, represent a significant leap forward in imaging technology. The ability to achieve high resolution without lenses opens doors to a wide range of possibilities, from detailed forensic analysis to non-invasive medical diagnostics.