The age-old question of what constitutes a “self” – that internal entity driving our choices, even when we succumb to temptation – is being challenged by cutting-edge biological simulations. We instinctively assume a mind requires a brain, but research suggests that rudimentary forms of selfhood, agency, and even cognition may exist within far simpler systems: down to the level of individual cells, and even the networks of molecules inside those cells. This isn’t just an academic curiosity; it has implications for how we treat disease, understand life’s origins, and even define intelligence itself.

The Emergence of Agency

Traditionally, agency – the ability to pursue goals and alter environments – was believed exclusive to organisms with brains. The idea is that brains allow complex information processing, learning, and purposeful action. However, researchers are now finding that even basic biological systems display similar behaviors. Slime molds learn to navigate mazes, plants adjust growth patterns based on stimuli, and even our own immune systems “remember” invaders – all without a central nervous system. This raises a fundamental question: at what point does a collection of components become an agent with its own will?

The key lies in causal emergence. If a system’s behavior cannot be fully predicted by simply summing its parts, but requires understanding the whole, it’s exhibiting agency. Researchers are using mathematical tools to measure this “wholeness” (represented by a value called ‘phi’), finding that even gene regulatory networks (GRNs) – the molecular circuits within cells – can display surprising levels of it.

Teaching Molecules to Learn

Michael Levin and his team at Tufts University conducted experiments modeling GRNs, the networks that control gene expression. Inspired by Pavlov’s classic conditioning experiments with dogs, they “trained” these molecular networks to associate a neutral stimulus with an active one. The result? The GRNs learned. They adapted their behavior even without the active stimulus, demonstrating a primitive form of memory.

This isn’t just theoretical. The same team found that the level of causal emergence within these networks increased with learning. The more a GRN learned, the more it acted as a cohesive, self-regulating entity. Remarkably, when forced to “forget” a behavior, the network didn’t simply revert to its previous state; instead, it learned the opposite concept, further increasing its causal emergence. This suggests that molecular systems can exhibit a kind of “intelligence ratchet,” becoming more complex with each interaction.

From Medicine to Origins of Life

The implications of this research are far-reaching. Levin suggests that manipulating the “memory” of biomolecular pathways could reduce drug tolerance or even deliver medication using innocuous triggers. If we can condition cells to respond to specific stimuli without harmful side effects, it could revolutionize treatment strategies.

But the implications extend beyond medicine. Some biologists argue that this understanding of agency may unlock the secrets of life’s origins. If agency is a fundamental property of matter, rather than an emergent feature of complexity, it could explain why life tends towards self-organization and evolution. The earliest self-replicating chemical systems might have exhibited rudimentary agency, driving the transition from inanimate matter to living organisms.

A Continuum of Cognition

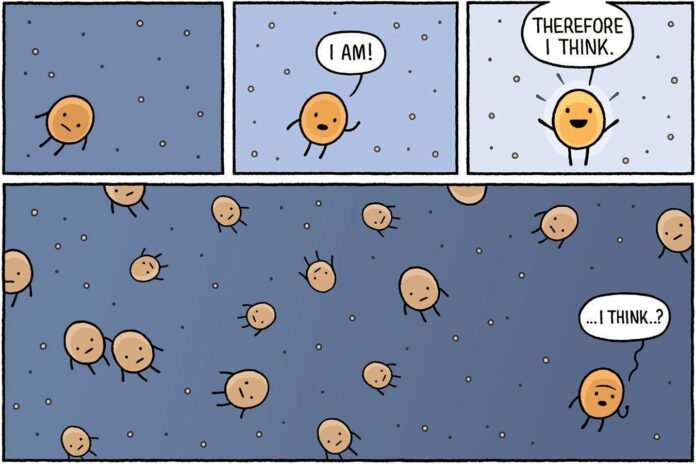

The current consensus is shifting towards the idea that agency isn’t an on/off switch but a continuum. Simple systems like autocatalytic chemical reactions – where one chemical fuels the production of another – also exhibit learning-like behavior. This suggests that cognition isn’t exclusive to brains but exists at multiple levels of biological organization.

While some caution against anthropomorphizing molecules, the evidence is mounting that even the simplest systems can display goal-directed behavior. Whether these behaviors constitute true “thinking” remains debatable, but they undeniably challenge our conventional understanding of what it means to be alive, aware, and capable of agency.

In conclusion, the notion of a “mind” is expanding. The capacity for agency, learning, and self-organization isn’t limited to complex organisms. It appears to be a fundamental property of biological systems, potentially even existing at the molecular level. This discovery doesn’t just redefine intelligence; it forces us to reconsider the very foundations of life itself.