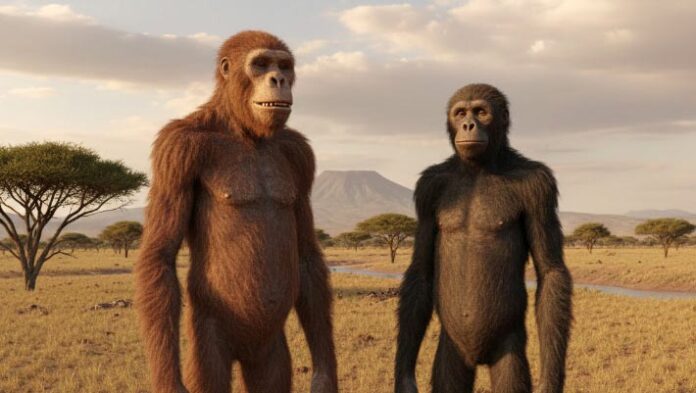

New fossil evidence confirms that two distinct species of early hominins, Australopithecus deyiremeda and the more famous Australopithecus afarensis (the species of “Lucy”), co-existed in Ethiopia roughly 3.4 million years ago. The discovery, based on a remarkably well-preserved foot fossil dubbed the “Burtele foot,” adds crucial detail to our understanding of early human evolution.

A Foot in Time: Confirming Two Species

For years, paleontologists debated whether the Burtele foot represented a unique species or simply variation within the Australopithecus afarensis lineage. Initial findings in 2009 hinted at differences, but solid confirmation required more evidence. Researchers have now definitively linked the Burtele foot to Australopithecus deyiremeda, a species previously identified from teeth found in the same region. This means that, contrary to earlier assumptions, the human family tree wasn’t a simple linear progression, but a complex bush with multiple branches living in the same territory.

This co-existence is significant because it challenges the idea of a single dominant hominin species at any given time. The presence of two distinct groups suggests that early hominins were more adaptable and diverse than previously thought. The fact that these species shared the same landscape implies competition for resources and highlights the selective pressures driving early human evolution.

Walking in Different Ways: Primitive Features Remain

Australopithecus deyiremeda possessed a more primitive foot structure than Australopithecus afarensis. Notably, it retained an opposable big toe – a trait crucial for climbing trees. While capable of walking upright, its gait differed from modern humans; the species likely pushed off with the second toe instead of the big toe.

This discovery reinforces the idea that bipedalism evolved in multiple forms before settling into the modern human stride. The presence of both an opposable and an adducted (non-opposable) big toe within the same time frame demonstrates that walking on two legs wasn’t a singular, fixed adaptation. It was a flexible trait, shaped by varying environmental demands.

Dietary Differences: A Mixed Menu

Isotopic analysis of teeth linked to Australopithecus deyiremeda revealed a diet leaning more heavily toward C3 plants – resources from trees and shrubs – compared to Australopithecus afarensis, which incorporated more C4 grasses and sedges. This suggests the two species occupied slightly different ecological niches, potentially reducing direct competition for food.

The dietary split emphasizes that even closely related hominins could exploit different resources within the same environment, contributing to their long-term survival. Further study of dietary habits could reveal how these early species carved out their own evolutionary paths.

Juvenile Growth Patterns: Unexpected Similarities

A recently discovered jawbone of a 4.5-year-old Australopithecus deyiremeda juvenile showed growth patterns similar to those observed in Australopithecus afarensis and even modern apes. This suggests that despite anatomical differences, early hominins shared fundamental developmental characteristics.

This surprising consistency in growth indicates that certain biological constraints likely influenced the evolution of these species, regardless of their divergent adaptations. It implies that some aspects of early hominin development were deeply rooted in their evolutionary history.

Ultimately, the confirmation of Australopithecus deyiremeda alongside Australopithecus afarensis rewrites our understanding of early hominin diversity. These findings underscore that human evolution was not a straightforward journey, but a complex interplay of adaptation, co-existence, and competition in a dynamic ancient landscape.